If I ever get the time together, I swear to god, I'm writing a book. This book will trace a certain geneology. It's one that Marshall McLuhan wrote all about already, really, but since I come upon it without him I don't mean to let that shut me up. It's a geneology that goes something, sort of like, this:

All of the above stories strip down the meaning of a person to a radical desire. And in the space of that desire some or most of the stuff we incidentally associate with people, with the business of being a person, is stripped away. Artificiality, or an embrace of the artificial, frequently appears...probably because the characters in these stories are all about action, and so often embrace tools that can accomplish these actions no matter the cost.

I�m making this sound more esoteric than it is. And what follows is just a shred of what I mean.

An initial mumbling on the politics of cyberpunk. May 27th, 1999

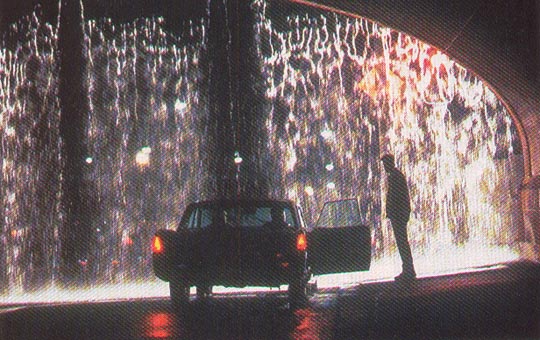

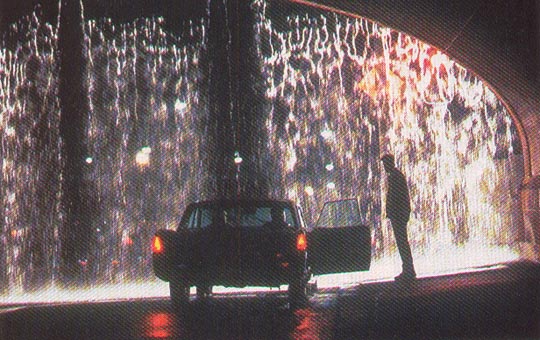

Murakami's story is not the only one to deal with this kind of weirdly empowering acceptance of artificiality. Heat, too, that by-now-dusty-in-its-video-jacket, too earnest, too long, ultimately flawed film, also skates this obsidian surface, in the person of Robert De Niro�s character. DeNiro plays the perfect modern gangster; perfect because no longer really human. His character has reduced himself to pure functionality � a flesh and blood algorithm. He does jobs, but has no desires about them � and so, because he has the strength to walk away from anything, can never be caught. His profits are like a river flowing around him, water through the fingers of an always open hand; you look at the suit on his body and know that he knows it's just a thing. He�ll have it until he doesn�t, and then there�ll be another, because his talent at his job ensures this � not that he can have things, but that he can ignore them. They can be featureless, and he can let them go. His house is one of the film's most prescient object lessons. Wholly unfurnished, it's a dojo-like box on Venice beach, all black lines and glass. At one point Val Kilmer�s character crashes there overnight and our man knows it as soon as he walks in the door because the lines are different. The emptiness of the house furthers functionality � it�s its own alarm system. It�s not a home � it isn�t a repository of stuff the self has attempted to imbue with spirit. Instead it�s a thing that functions as such and so just purifies the focus on the character. To find him, you can�t look at the house, the clothes, the car, the anything; of him, he�s all there is. De Niro�s character presents a gorgeous question � what might become possible, what might come to you, if you give up everything? If you merge yourself absolutely with actions and not things, machines and not persons? Frightened of its own growing conclusions, the narrative makes a last minute track-change and goes for didacticism and grossly stupid �tragedy.� But it�s impossible to watch the thing and not be drunk with its possibility, to just embrace the outermost edge of The Way Things Are Going and see what comes of it.

And thus, the Matrix. Ostensibly, it presents a world in which persons and machines are engaged in the bitterest struggle, but that a blind, a weak one at that. Terminator, T2, maybe, presents a world in which people and machines are at odds, and the people look like it, living primitively around little fires, rubbing together their trembly coal-smudged hands. In the Matrix, the �free� characters live in barracksy semi-comfort, yes, but only incidentally, only part of the time. They aren�t anti-technology, far from it. They�re crazy hybrids who, like De Niro�s gangster, have abandoned a certain amount of humanity, or normal human reality, in exchange for a great leap in technologically assisted ability. They wear prison clothes on their little ship, but the ship isn�t really where they live; they live in programs, in which they wear whatever they can think of. Their lives on the ship seem a little gray, but those aren�t their real lives, because they live in programs, in which they have superhuman abilities. And part of the point of leaving the system, being freed from the �matrix,� is to gain those abilities. They may wish to destroy the Matrix in which most of humanity is living, but it seems highly unlikely they mean to destroy technology itself. If they ever succeed, it will probably be in order to have more time to play in the virtual dojo, to jump off more virtual skyscrapers and run on more virtual walls.

The Matrix, in short, asks the same scary-exciting thing as Heat and Dance Dance Dance - if, instead of railing as the present and future in all these useless, too-familiar ways, we accept the furthest edge of possibility, of machine-assisted ability, what can we become? The question is interesting not as�a normative force (thou shalt be a fan of large-scale capitalism, thou shalt be a technophile), but because of the normative neutrality. It opens the way for narratives in which the nature of humanity has no predetermined limits, in which we can�t rely on the luddite technophobic picture of what it isn�t (brought by Jurassic Park, The Net, Virtuousity, and the latest journalistic embarrassment in Time Magazine), but can actually ask the question of what it is, and brave both its flimsiness and possibility.

The chance is there to unleash something new under the sun, again, just when I'd been mired in cable television and the predominant zeitgeist, immobile on the sofa and getting all depressed. Something's waiting.

Sadly, that doesn't mean I have any idea what it is.

Raymond Chandler to Neuromancer to Blade Runner to the pilot of Max Headroom. And then from The Long Goodbye (Chandler again)to J. Lethem's Gun, with Occasional Music, to H. Murakami's Dance Dance Dance. From Blade Runner to Aeon Flux to Heat, through Appleseed and Ghost in the Shell. (The overarching figure, really, is a character named Starkad, a Norse hero associated with Odin. He's kind of the patron saint of all hero's who lean towards the taciturn, and always achieve their goals, but inevitably get roughed up along the way. But more on this later, elsewhere, etc.) Somewhere amidst all of this is Martin Cruz Smith's Gorky Park, and the Matrix is now the most recent link in this mail-like-chain.

There�s this book, by Haruki Murakami � Dance Dance Dance. It�s an odd book about a loosely Marlowe-esque guy hunting for his girlfriend, notable mainly for its weird, lovely, singular, weightlessness. In his fictional universe, which is ours more accurately that I�ve seen anyone else depict, the interchange of persons and corporations is simply total. To struggle against it is not only useless but invalidating. �It's the way of the world - philosophy starting to look more and more like business administration,� he writes, neither pleased or dismayed. He's not the first to have made the statement, but he's the first to do so sneerlessly. In Murakami's world, the massive waste and occasional criminality that characterizes large scale capitalism isn�t Bad. It�s neutral. And this is an amazing statement, because to have one's futile, fulminating rage against the System obviated, just washed away, is an outright shock. I lose so much energy hating Ted Turner, Blockbuster, Starbucks. And my hate, having no affect, is ultimately to their advantage. Murakami�s book is a kick in the head, because it says, this hate is useless. Take these things as givens - not as the wave that's breaking over you're head, but the water you're floating on. And now that you have your agency back, what are you going to do?